2020

HOLLOW

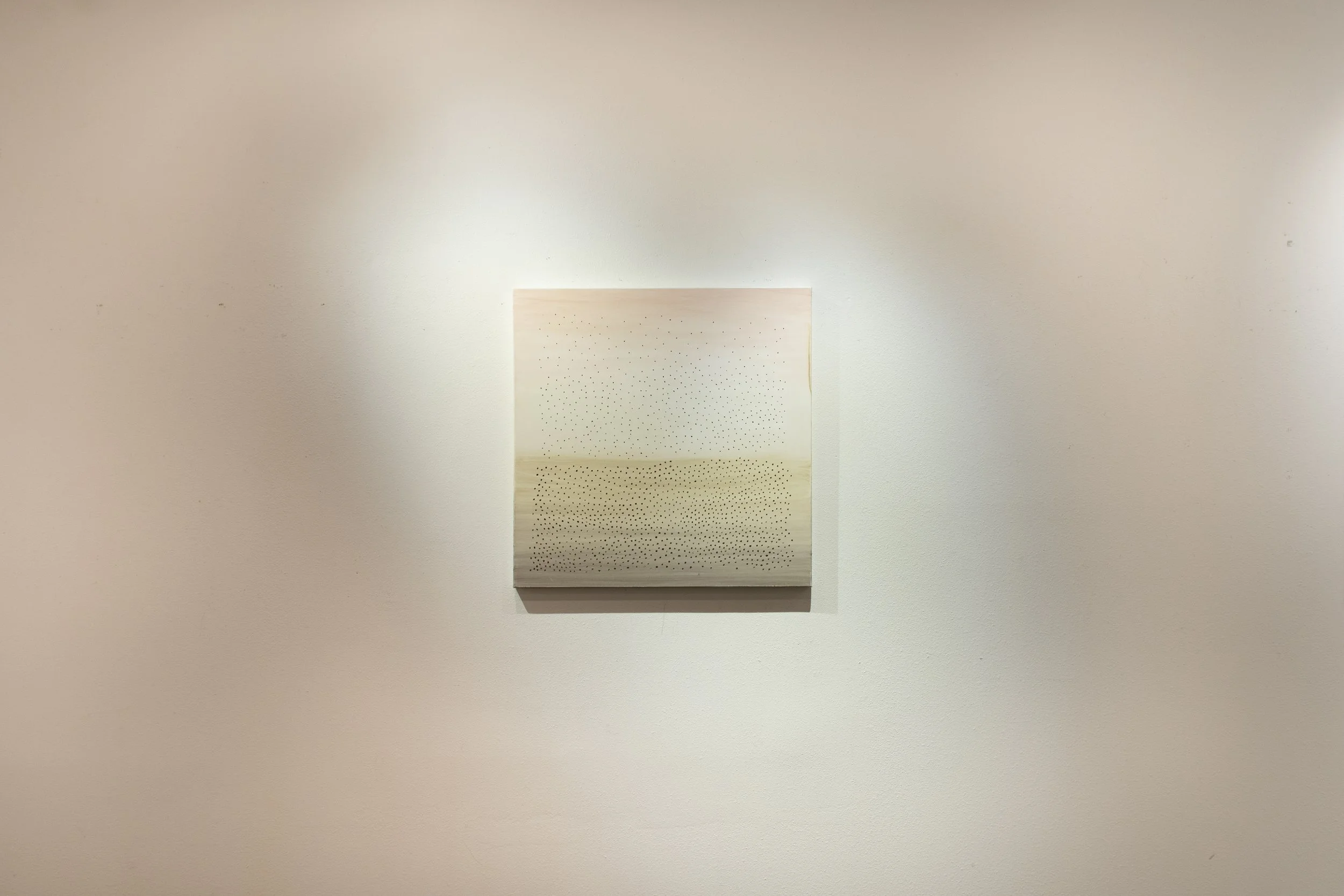

Spectre#1 oil on canvas ,handcut, 61x61cm,2019

Spectre#2 oil on canvas, handcut, 61x61cm,2019

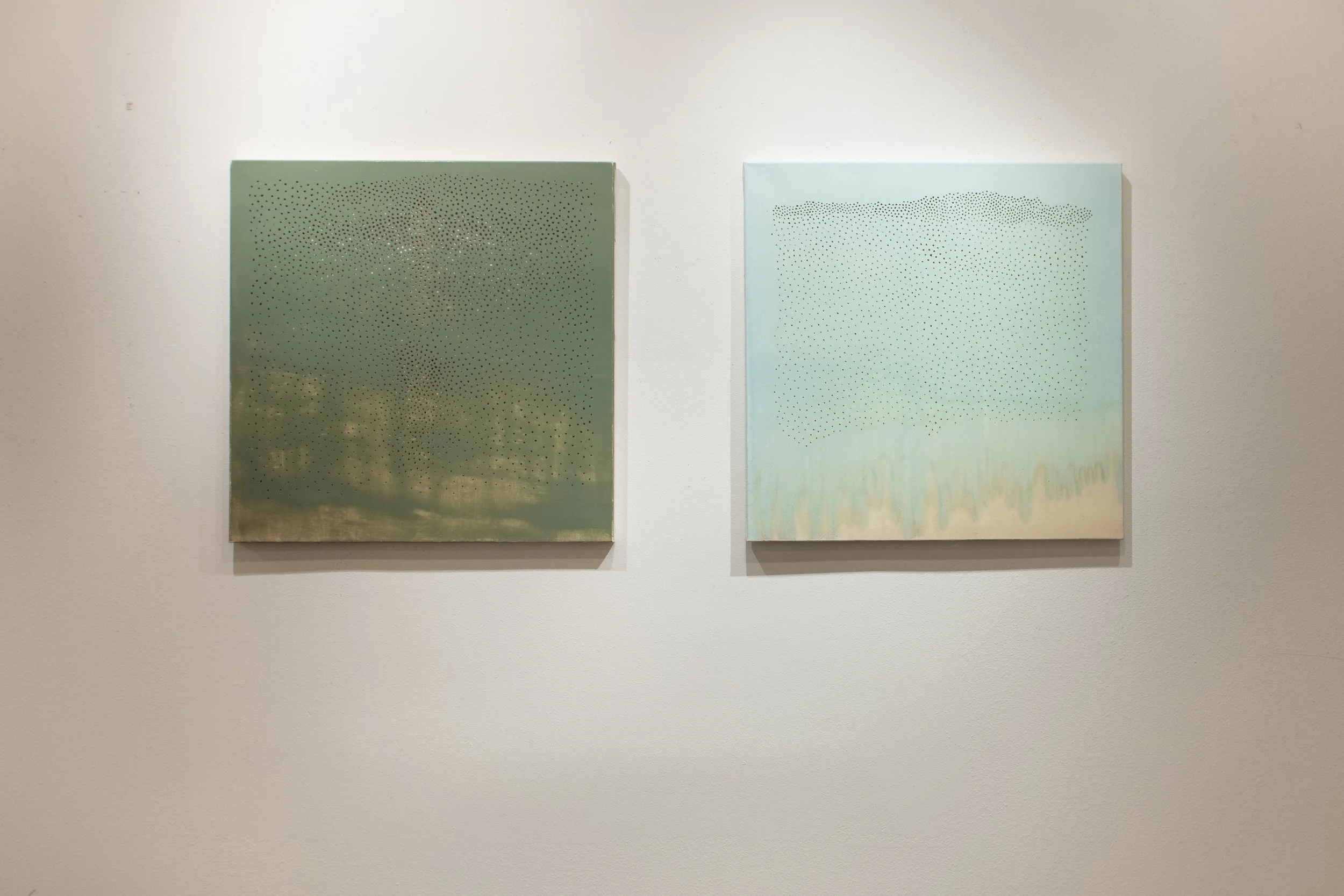

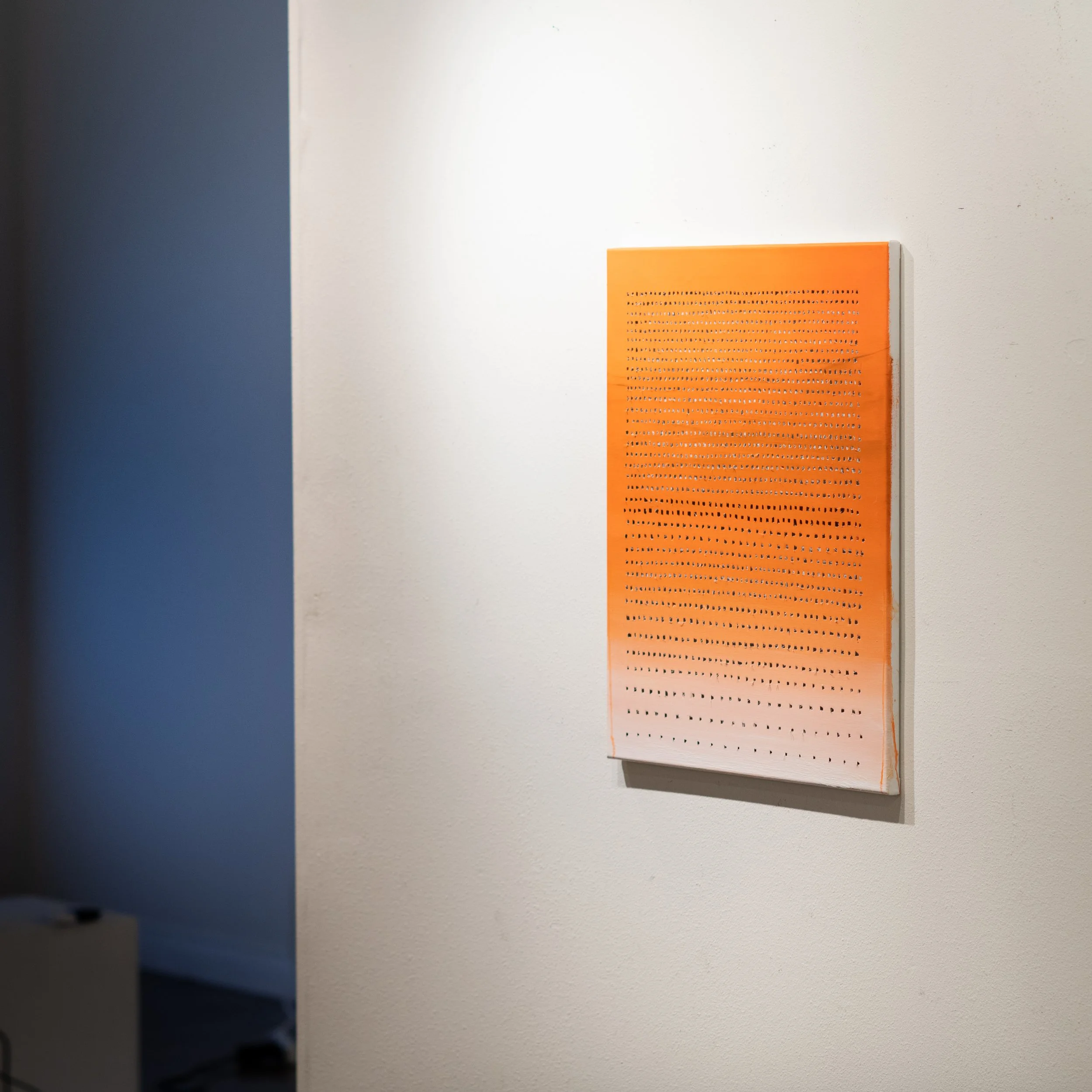

Spectre3 oil on canvas, handcutting, 100x100cm, 2020

Spectre4 oil on canvas, handcutting, 100x100cm, 2020

Spectre5 oil on canvas, handcutting, 100x100cm, 2020

Spectre6 acrylic on canvas, handcutting, 53x45cm, 2019

Spectre7 acrylic on canvas, handcutting, 53x45cm, 2019

Detail Image of Spectre 3

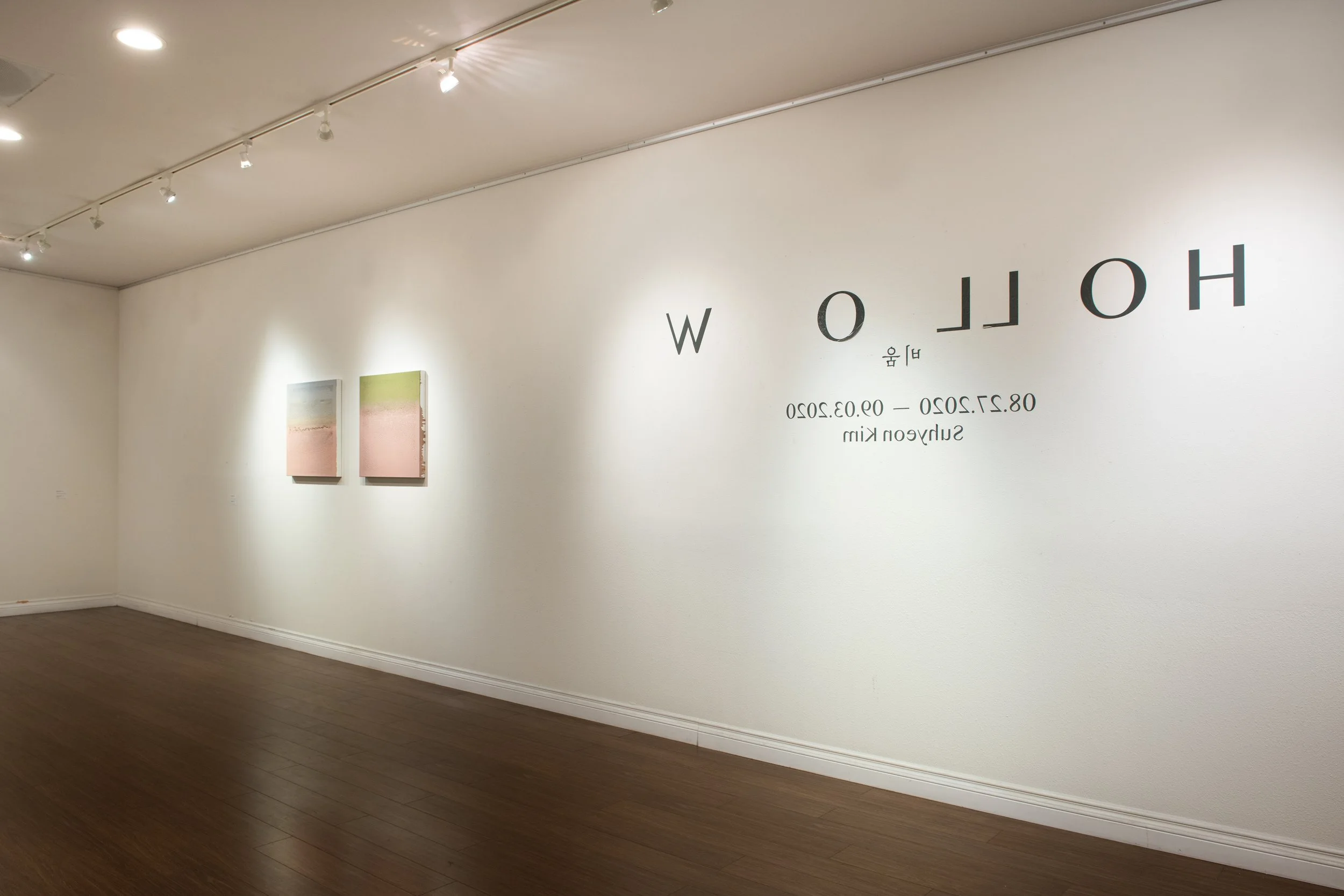

Installation View 1

Installation View 2

Installation View 3

Installation View 4

Installation View 5

Installation View 6

Installation View 7

Installation View 8

Installation View 9

Installation View 10

Installation View 11

An Ordinary Sunrise

About Suhyeon Kim’s ‘Hollow’

Lee Sangyoon (Art historian)

1. Suddenly made hollow hole

Suhyeon Kim holds her solo exhibition 《Hollow》 in LA’s Koreatown, 2 years after the exhibition 《Denial before, indeterminate still》 in 2018. She seemed to vanish then and suddenly shows up to bring word of her exhibition.

The most distinctive change on her new works is not only remarkably brightened and gentle colors but also adjustment of holes’ shape that felt even painful. Exotic colors inspired from desert also embodied ponderosity and honesty with oil painting, instead of existing acrylic coloring. Though the work of ‘digging’ to make holes on canvas using a knife and make people recognize the canvas not as a stage for reproduction but as a substance itself still is the most representative characteristic of Suhyeon Kim’s painting, the overall atmosphere of her works this time is totally different from before. Holes that are now relatively even in size and arranged in an organized way are so away from logic and argument that it recalls Vladimir’s lines that read “But habit is a great deadener.” in Waiting for Godot which never left her hand. The digging work started from 2006 and she is finally skilled after 15 years, which cannot be seen as horrible pain or impulse of destruction any more, or practice of cool-headed reason against tradition either. Suhyeon Kim’s digging holes seems to be hypnotized – it is repetitive, unconscious, drowsy and aesthetic at the same time.

2. Daily life paused due to possibility of death

The change described above appears to begin at a crack and break in dailiness. Her trip to US in 2018 formed spacetime like in a vacuum, which Suhyeon Kim likened to ‘hollow.’ In addition, the pandemic that started in February 2020 actualized unexpected hollow and dished discontinuity, in other words, a pause of life attributed to death. The artist note that says “street without any cars and people, empty gallery, hollow exhibition with no hope for viewers” shows her observation of surreal circumstances in LA’s empty streets without cars or any human traces, closed shops and exhibition with no viewers. It is like a record on life premised on death. She said daily life on pause triggered by the pandemic reminded of deeply sunken, empty space as if a number of people were sucked in all together. Suhyeon Kim stated that this sudden pause may be a state where life and death coexist or perhaps, a moment when death is more vivid than life.

As in lines of Waiting for Godot that read “They give birth astride of a grave,” huge hollow caused by life destined to death and possibility of death made the artist focus on the most essential and original question. It is supposed that the question about the origin has actually lingered around her since a pilgrimage to a desert (Joshua Tree National Park) started in 2019, not because of the pandemic.

A desert in American West where Suhyeon Kim stayed was a ‘off-grid’ place out of GPS tracking, which was like cracked dailiness or a huge sunken pit and at the same time, undefined or undetermined dimension that walked a fine line between reality and surreality. Landscape of the desert stuffed as a pristine form itself also was a place where paused time lasted forever and as in the pandemic, it showed nature that did not belong to either death or life. These two, death and life, could coexist as equivalent values in the dimension of vacuum. What the artist faced here was an existential question. In a desert and an empty city where “nobody comes or leaves and nothing ever happens” and in the pandemic as well, the artists seems to have faced greatness of death, beauty of melancholy or finiteness of her existence.

3. Hollow that is open to anyone but cannot be faced by everyone

Through cracks and hollow space made due to death, the artist approached fundamental issues such as cosmic nature, transcendence, limitations of existence and perpetuity that are open to anyone but cannot be faced by everyone. Questions that had never been experienced in daily life, or, had never been necessary for daily life, shook firmness of existence, which increasingly hazed assertive ‘me’ and overlapped objects that ‘I’ looked at with ‘myself.’ While the existence scattered this way, objects that were easily perceived and recognized also became faint. For example, the speed of time we perceived and experienced in the desert was totally different from that of daily life and notions that we had conventionally recognized were also redefined. A video work <An Ordinary Sunrise> at this exhibition shows how the passage of time is diversely experienced in a desert and how everyday and ordinary landscape is differently recognized. She found in the desert that death was not an end and life was not always brilliant. Considering the changes above, Suhyeon Kim’s works definitely did come closer to nihilism that before but had difference from common melancholy. The distinctive difference here is that her works do not define death as the finality or present death as something charming but humbly accept both life and death on a border where the two are overlapped. This difference is supposedly an outcome that Suhyeon Kim’s consistency to put off making definitions and determination was reflected to expanded sight beyond personal dimension.

3. Simple and great proposition

The ‘Spectre’ series appeared in the process that dilutes the border between everything that cannot be defined or determined any more and has been otherized from me. Given the aforementioned background and process, Suhyeon Kim’s ‘Spectre’ series could be understood as an indicator which belongs to either of existence and non-existence, death and life or on which the two notions are overlapped. I suppose that it would be human existence exposed through the huge hollow hole which is not only the artist’s personal symbol but that of mankind. In the presence of this existential question, the artist chose acceptance over an answer. As the value judgment of whether her work was of canvas or cut pieces or order of rank became one of consuming debate upon the ‘Spectre’ series on which the holes returned to similar forms and meaningless repetition, the proposition faced at the hollow pit inhaled all the disputes at once. Life and death, the simple but great proposition, shows itself through Suhyeon Kim’s painting but does not give us any answer.

“They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.”

Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett

김서연의 ‘비움(hollow)’에 대하여

이상윤 (미술사)

1. 갑자기 생긴 빈 구멍

2018년 《부정의 이미, 부정적 아직》 전시 이후 2년 만에, L.A의 코리아 타운에서 김서연의 개인전 《비움 Hollow》이 열린다. 사라지듯 떠났던 작가는 이번에는 불현듯 나타나 전시 소식을 전했다.

눈에 띄게 밝아지고 부드러워진 색감뿐 아니라, 고통스럽기까지 했던 구멍의 형태가 정돈되었다는 점은 이번 신작에 나타난 가장 단적인 변화다. 또한 사막에서 영감을 받은 이국적인 색들은 기존의 아크릴 채색이 아닌 유채(油菜)로 묵직한 무게감과 정직함을 부여하였다. 칼로 캔버스 천에 구멍을 내, 캔버스가 재현의 무대가 아닌 물질 그 자체로 인식하도록 하는 ‘뚫기’ 작업은 여전히 김서연 회화의 가장 대표적인 특징이나, 대체로 작품의 분위기는 이전과 전혀 다르다. 비교적 일정해진 크기와 정돈된 배치로 변화한 구멍들은 작가가 지니고 읽었다는 『고도를 기다리며 Waiting for Godot』의 “습관은 우리의 이성을 무디게 한다”는 블라디미르의 대사를 상기시킬 정도로 논리와 주장에서 멀어졌다. 2006년부터 시작된 구멍 뚫기 작업이 15년 만에 비로소 손에 익숙해져, 더는 처절한 고통이나 파괴 충동으로만 볼 수 없으며, 전통에 저항하는 냉철한 이성의 실천 역시 아닌 듯하다. 김서연의 구멍 뚫기의 행위는 이제 최면에 걸린 듯, 반복적이고 무의식적이며, 동시에 나른하면서 미적이다.

2. 죽음의 가능성에 의해 정지된 일상

위와 같은 변화는 일상성에 생긴 균열과 틈에서 시작된 것으로 보인다. 2018년의 미국행은 작가에게 진공 상태와 같은 시공간을 조성했다. 김서연은 이것을 ‘속이 빈(hollow)’으로 비유하였다. 게다가 2020년 2월부터 시작된 팬데믹(pandemic) 현상은 속이 비고, 움푹 꺼진 예기치 못한 단절 즉 죽음에 의한 삶의 일시 정지(pause)를 실제화하였다. “차도 사람도 없어진 거리, 비워진 갤러리, 관객을 기대할 수 없는 빈 전시”를 기록한 작가 노트는 인적뿐 아니라 차도 지나지 않는 L.A의 텅 빈 거리와 문 닫은 상점, 관객 없는 전시라는 초현실적 상황에 대한 그녀의 관찰이 담겼다. 그것은 죽음을 전제하고 있는 삶에 대한 기록과 같았다. 팬데믹이 몰고 온 정지된 일상은 또한 수많은 사람들이 일제히 빨려 들어가는 것과 같은 움푹 패인 빈 공간을 연상시켰다고 한다. 김서연은 이러한 갑작스러운 정지를 삶과 죽음이 동시에 존재하는 상태, 또는 어쩌면 삶보다 죽음이 더 선명한 순간이었을지 모른다고 설명하였다.

『고도를 기다리며』의 “산모가 무덤에 앉아 출산한다”는 대사와 같이 죽음이 전제된 삶, 죽음의 가능성이 야기한 거대한 구덩이는 작가를 가장 본질적이고 근원적인 질문에 주목하도록 했다. 사실 팬데믹 때문만이 아니라, 2019년부터 시작한 사막(Joshua Tree National Park) 순례부터 근원의 질문은 작가의 주변을 맴돌았던 것으로 생각된다.

김서연이 머물었던 미 서부의 사막은 GPS 위치 추적도 불가능한 ‘탈 좌표(off-grid)’의 장소로, 그녀에게 이곳은 균열이 생긴 일상성, 또는 움푹 패인 거대한 구덩이이자 동시에 현실과 초현실의 경계를 넘나드는 비규정적, 비결정적 차원과도 같았다. 또한 태고의 모습 그대로 박제된 사막 풍경은 그 자체로 정지된 시간이 영속하는 장소이면서 팬데믹과 마찬가지로, 죽음과 삶 어느 쪽에도 속하지 않은 자연을 보여 주었다. 죽음과 삶, 이 둘은 동등한 가치로서 진공의 차원에서 공존할 수 있었다. 여기에서 작가가 맞닥뜨린 것은 실존적 문제였다. “아무도 오지도, 가지도 않고, 아무 일도 일어나지 않는” 사막에서, 텅 빈 도시에서, 그리고 팬데믹 현상에서 작가는 죽음의 위대함이나 멜랑콜리의 아름다움, 혹은 자기 실존의 유한함과 마주하였던 것으로 보인다.

3. 누구에게나 열려있지만, 누구나 마주할 수는 없는 비움

죽음에 의해 생긴 균열과 빈 공간을 통해 작가는 누구에게나 열려 있지만, 누구나 마주할 수 없는 우주적 자연, 초월성, 실존의 한계, 죽음의 충동, 영속성 등과 같은 근본적인 문제들에 다가갔다. 일상에서 경험해 보지 못한, 아니 일상에서는 불필요했던 질문들은 실존의 견고함을 흔들었고, 그럴수록 확신적인 ‘나’는 희미해지고, ‘나’가 보는 대상들이 ‘나’와 중첩되었다. 이렇게 실존적 존재가 흩어지면서, 익숙하게 지각하고 인식하던 대상들도 희미해졌다. 예를 들면 사막에서는 우리가 지각하고 경험한 시간의 속도가 일상에서와 전혀 달랐고, 관습적으로 인식했던 개념들도 재정의되었다. 이번에 전시되는 영상 작품 <어느 평범한 일출(An Ordinary Sunrise)>에서도 역시 시간의 흐름이 사막에서 어떻게 달리 경험되는지, 그리고 일상적이고 평범한 풍경이 어떻게 다르게 지각되는지를 보여준다. 사막에서 죽음은 끝이 아니며, 생명이 항상 찬란하지만은 않았다는 사실을 알게 되었다. 위와 같은 변화를 볼 때 김서연의 작품이 이전보다 확실히 허무주의에 근접한 것은 사실이나, 여느 멜랑콜리와는 차이가 있었다. 죽음을 궁극으로 규정하지 않으며, 죽음을 매혹적으로 제시하지 않는 점, 단지 삶과 죽음이 중첩된 경계 위에서 양자 모두를 겸허하게 받아들이고 있다는 점이 분명 다르다. 아마 이 차이점은 규정과 결정을 보류하는 김서연의 일관됨이 개인의 차원을 넘어 확장된 시각에까지 반영된 결과이지 않을까 생각한다.

3. 단순하고 위대한 명제

이처럼 더는 규정할 수 없고, 비결정적이며, 나와 타자화된 모든 것 사이의 경계가 희석되는 과정에서 이 ‘유령(spectre)’시리즈가 등장하였다. 위와 같은 배경과 과정에 비추어볼 때 김서연의 ‘유령’ 연작은 존재와 존재하지 않음, 죽음과 삶 등 양자 모두에 속하거나 또는 두 개념이 중첩된 상태의 지시체로 이해될 수 있을 것이다. 그리고 비단 작가 개인의 상징뿐 아니라, 모든 인간의 상징체 곧 커다란 빈 구멍을 통해 드러난 인간의 실존이 아닐까 한다. 이러한 실존적 질문 앞에서 작가는 답 대신 수용을 선택하였다. 뚫린 구멍들이 비슷한 형태와 무의미한 반복으로 회귀한 유령 연작부터는 캔버스 화면이냐, 잘린 조각들이냐에 관한 가치 판단이나 위계질서마저 소모적인 논쟁의 하나가 되어버린 것처럼, 빈 구덩이에서 마주한 명제는 논쟁들을 일시에 흡입해 버렸다. 삶과 죽음이라는 단순하지만 위대한 명제는 김서연의 회화를 통해 단지 그 자신을 보일 뿐, 답을 주지는 않는다.

“산모는 무덤에 앉아 출산을 하고, 빛은 잠시 동안 비추고, 곧 다시 밤이 오지”

사무엘 베케트(Samuel Beckett), 『고도를 기다리며』 중에서